the trap door is the only option

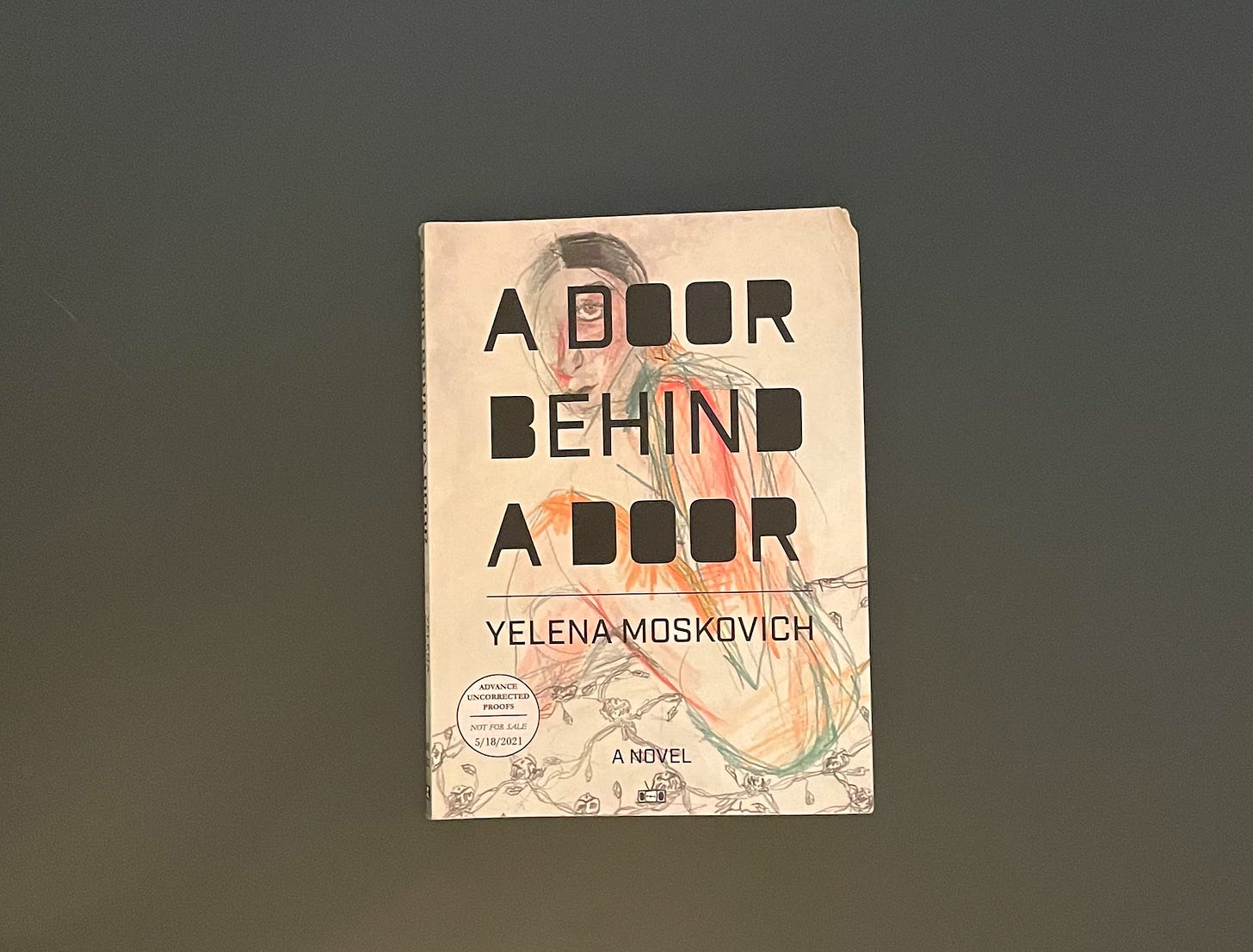

Yelena Moskovich's A Door Behind a Door is 7.5 x 5.75 x 0.5 inches & 188 fractured pages.

Welcome to Purse Book, a weekly newsletter about reading hot little books & being a gal on the go. If you haven’t already, you absolutely may subscribe now.

Yelena Moskovich’s novel A Door Behind a Door begins, as all lives must I guess, with a baby, a baby who is described in the most fantastic way a baby could be described: “I was a fat baby. I was lying in my crib like an egg yolk.”

Olga (yolk baby) lives on the sixth floor of Ukraine apartment complex. Before emigrating with her family in the 1991 Soviet diaspora, a troubled neighbor boy named Nicky kills a woman in the apartment across from them. This violence lingers like a vague ghost, until decades later Olga is in Milwaukee, back on a sixth floor apartment, living with her girlfriend. She’s in her languorous twenties, being lusty and irresponsible and cool, when she gets a call in the middle of the night from the young murderer Nicky.

Absolute narrative havoc spills forth. It’s like a trap door opens underneath Olga’s feet, replacing what she thought was solid, sturdy ground. Who is dead, who is alive, who is in prison, is the prison real: questions I know to ask but couldn’t confidently answer.

A Door Behind a Door is a puzzle that’s also a kaleidoscope. The action and the images are stacked and then refracted off mirrors. There’s a hint of a promise that if you get the pinwheels to align just right, you’ll see the clear, finite truth. It’s like trying to solve a puzzle but the table is spinning the whole time. I never felt like I solved it, but I’m impatient with puzzles. Or that’s not right: I just have no incentive to complete puzzles, because I’m evolved enough to find satisfaction with the unresolved. The impression of the puzzle unsolved is enough, and it’s an impression that’s so distinct in A Door Behind Behind a Door.

A Door Behind a Door, as the title demonstrates, is about unfinished business that can never be finished, how certain people will keep entering each other’s lives, how nothing can be locked away forever. It’s a story about fate, but it’s also a story with dizzying fractures.

This combination—of fate and infinite possibility—rubbed against a Big Theory I’ve heard about contemporary narratives. I listened to an interview with N. K. Jemisin last month, where she talked about the notion of “the multiverse” replacing the notion of “fate” in fiction. The multiverse—an idea about countless worlds coexisting—reflects a world of overwhelming choice and entangled contingency. Meanwhile, stories about fate involve accepting or battling the preconceived will of a higher power. Put against the multiverse, fate seems like a little old-fashioned choice now. The narrative arrangement of A Door Behind a Door feels exceptional, and daring, and also effortlessly smart for saying: Obviously, You Don’t Have To Choose.

ENOUGH PHILOSOPHY, I WANT TO TALK ABOUT STYLE. A Door Behind a Door has style! Most apparently, Moskovich is in love with Headings and now I am too. Sections, which range from a couple words to a few paragraphs, almost all come with their own Heading. It’s a strategy that seems Emphatic about Everything. The Headings are a relentless attempt to assert order that only ends up creating more chaos. It feels extremely well matched to a story about characters whose lives keep getting mixed up.

You know, I realize I’ve fallen back into being philosophical about this book. I can’t help it, it is the trap door I find myself upon.

And, prepare yourself, there are books behind this book! Yelena Moskovich has recommended a handful of her favorite very short Official Purse Books.

Love by Hanne Ørstavik

The Transmigration of Bodies by Yuri Herrera

Life Went On Anyways by Oleg Sentsov

Klotsvog by Margarita Khemlin

The Time: Night by Ludmilla Petrushevskaya

When Death Takes Something From You Give It Back by Naja Marie Aidt

I have a favorite title, can’t help myself, hope we have the same one.